One dark night in the mid-1970s, Chief Thomas N. McIntire, Jr., cruised downtown Elkton. As the midnight hour neared, the police radio was silent, but suddenly it crackled to life with the most urgent dispatch, an officer was in trouble. A man was struggling with the lawman over by the railroad station. The other cop prowling the town that night signaled that he was rolling from out on Route 40 and would be there in three or four minutes.

Hitting the siren, the 50-something chief glanced at his partner, making sure he was ready for action as they would arrive ahead of the other unit. Screeching up to the depot, McIntire sprang into action helping cuff the man, while his partner maintained a calm, watchful eye over the ruckus.

Back at the station McIntire’s sidekick was full of energy, happy and eager to be on the job, while the patrolmen booked the perpetrator. Duke was just the type of partner the top cop in the county seat wanted at his side. Although officially not a member of the nine-member force, the Black Labrador and the chief were inseparable.

It was all part of the job as lights went down in Elkton and the graveyard shift got underway. About the time everyone else was falling asleep, two of the chief’s men started their workday. The retiring watch briefed them, the paper work was shuffled, and plenty of coffee was available for the long, silent hours ahead. The two beat officers, prowled the alleys and back streets, keeping a watchful eye on the night and waiting for the dawn in the sleeping town.

But McIntire’s routine was different. After finishing a full day’s work, he went home for the evening. But he jumped back into the cruiser sometime after dinner to make evening rounds, checking on the town and his men. Whenever Duke saw the chief climb into the car, he sprang into action, jumping into the vehicle. The Chief and his 50-pound lab were a pair around Elkton in the 1970s. Duke, that friendly Labrador, accompanied the chief while he was checking dark, lonely alleys and backing up his men. Eventually, often in the wee hours of the next day, things quieted down once barrooms closed and people settled in for the night so the chief returned home. He got up and started all over again the next day, for administrative matters had to be taken care of during the workday.

When McIntire started on the crime beat in August 1951, he was paid $1.25 an hour. There were no radios to receive dispatches or to summon backup. Typically, a shift involved many foot patrols downtown and periodic rounds of the outlying areas. The only prowl car was parked nearby at North and Main streets.

Besides the fact that most activity took place in the business district, there was another reason the officers remained downtown. A red light on top of a telephone pole at the main intersection signaled that a citizen was calling for assistance. When the telephone operator received a complaint, she turned the light on and the policeman rushed over, to answer the police phone.

All too often, McIntire once remarked, you would be siting in the squad car at the corner of North and Main, keeping an eye on traffic and that phone. In the middle of a downpour or thunderstorm, the light would flash, so you got out in the rain to answer it. After saying “Elkton Police” someone respond by asking about how to get married in Elkton.

“In a few years, they put in a radio system so we could crisscross the town while our dispatcher, the water plant operator, took calls. With that communications system, we thought we were very modern,” McIntire recalled. “I was sworn in as chief of police in 1962 when the town was putting on a push to modernize the force. My salary jumped to $80 a week.

“I had four full-time and two part-time men and my goal was to have 24-hour patrols since the dark hours before dawn were often uncovered. For a holding cell, we handcuffed the prisoner to a pole in the police station while we investigated the matter or processed them before hauling the person to the county jail.” It was supporting the second floor. The work in those days was largely routine. “Traffic problems, simple assaults, drunkenness, loitering, minor thefts, and disorderly conduct made up the bulk of the few calls we’d get. We also had a little trouble with kids.”

Despite the easy going pace of county seat town with 5,000 people, there were some alarming incidents that jolted the routine. One Sunday night in 1963, as flashes of lighting fleetingly illuminated a cold, rainy December night, one of McIntire’s officers prowled the empty streets when, without warning, a dreadful explosion shook the entire town as a fireball, plunging into a rain-swept cornfield, chased away the darkness. Night turned to day and residents worried that a Soviet missile attack might be underway while the fire siren wailed out its urgent call.

“I rushed to the firehouse since I was also an assistant chief in the fire company. We weren’t sure what had happened, but on a cornfield just outside town, we located large craters, burning fuel, parts of the Boeing 707 fuselage, and a widely scattered debris field. We soon learned that a Pan-American plane had crashed and eventually found out that 81 people perished in that explosion. Once we determined there wasn’t much to do since rescue and ambulances weren’t needed, I went back into town to assist my officers. Traffic control was a major problem, the FBI was coming in, a morgue had to be set up, and a perimeter set-up, things like that.”

Another time in October 1965, a fireball loomed high up into the sky at the edge of the town, almost looking like a mushroom cloud. “A freight train containing chemical and petroleum tankers jumped the tracks and there were enormous explosion. We had to evacuate a portion of the town because of the fear of explosions and the size of that fire,” McIntire said.

After 28 years in law enforcement, 18 as chief, McIntire decided it was time for a regular office job. So at 55 years of age, he became the supervising commissioner for the district court.

Reflecting on his 28 years in law enforcement, he said, “As a young boy growing up in Elkton, I still remember the old man who was our first chief of police, George Potts [1908-1935]. All he had to do was glance at one of us boys thinking of doing something wrong and we’d move right along. In addition to the little bit of crime that he handled, the town required the chief to oversee maintenance of the streets. By the time I retired we had a force of 14, computers connecting us to FBI and motor vehicle databases, and a criminal investigator.”

Chief Thomas McIntire had successfully guided the agency into the era of modern police work. The times, the 1960s, were challenging for law enforcement across the nation as administrators struggled with social upheaval, growing violence, new laws and attitudes, emerging technologies, and the changing times, but in Elkton his steady hand moved the department forward through this maze. He created a professional force with state-of-the-art methods that would have been most unfamiliar to earlier commanders.

For additional photos click here.

For additional historical photos related to Chief Thomas McIntire see this album on Facebook.

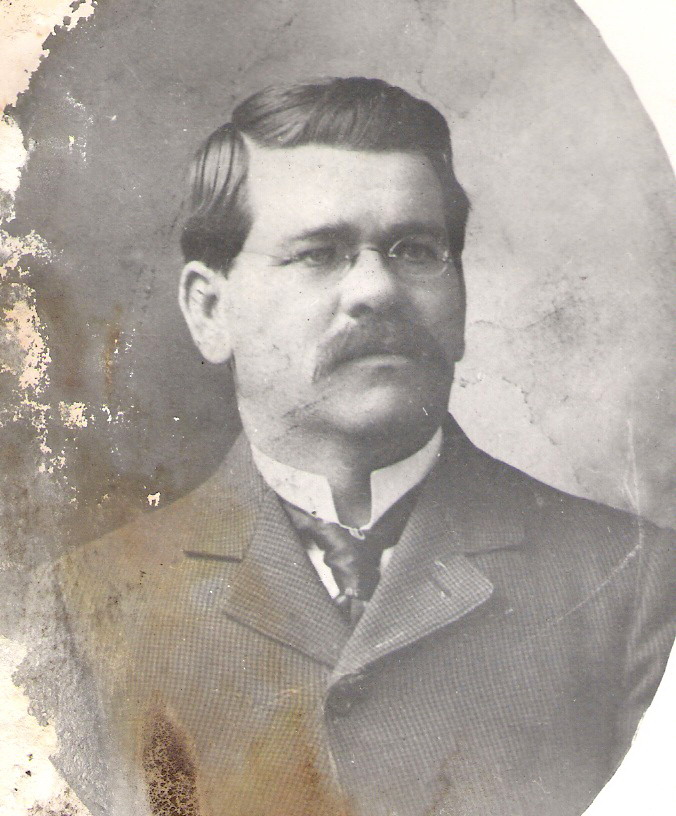

Elkton’s Early Police Chiefs, (Thomas McIntire, 1962-1980)